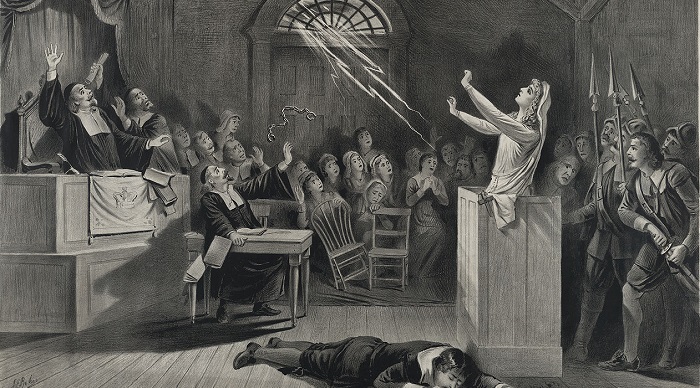

Fanciful representation of the Salem witch trials, 1892 © LoC

If I say the word “witch,” what imagery conjures in your mind? Wizard of Oz? Macbeth? Abigail Williams dancing in a Salem forest or Neve Campbell in thigh-high stockings? If it’s all pointy black hats, cackling in the moonlight, and magic potions made of frogs, then it’s high time you learn the truth about the old black magic. This Halloween, stuff your preconceived notions in the broom closet and dive into the dark, beating heart of Alex Mar’s terrific new book Witches of America.

For five years, Mar immersed herself in Paganism. Her fascination came about while she was making the 2010 documentary “American Mysticism,” in which she followed three Americans practicing alternatives religions: A Spiritualist, a Lakota Sioux, and a Feri witch named Morpheus, a wondrous red-haired “Big Name Pagan” who serves as the author’s primary friend, mentor, guide, and spell-caster.

Mar’s journey is fascinating. She takes readers to places most have never been, such as PantheaCon, an annual gathering at a San Jose DoubleTree, a Gnostic Mass complete with menstrual blood, semen and chicken livers, and to a Samhain festival of the dead where worshipers offer prayers and give thanks to ancestors who have left the mortal plane. And then have a hot tub.

The rituals move from light — going naked, a.k.a “skyclad” — to the dark, like one chapter that describes Mar hanging out with a necromancer who robs skulls from dilapidated graves. But at no time does Mar pass judgment on her subjects. The overriding theme of the book is to live-and-let-spiritually-live, but it isn’t solely out of journalistic objectiveness. What drives Witches in America is Mar’s longing to understand her own sense of belief/disbelief in other-worldly powers and how it relates to her everyday life. Like you and I, Mar struggles with relationships, career aspirations, and her place in the universe. Only she visits the Church of Satan to see if they have any answers.

At one point Mar is asked, “Are you a witch, or are you just… doing research?” Boil and bubble up a pot of eye of newt and toe of dog, and crack open Witches of America to find out. It’s a thought-provoking work that offers a much more substantial way to enjoy the spooky season than downing pumpkin jello shots in a Sexy Pizza Rat getup.

First, let’s set the mood.

Biographile: My hunch is that many readers, like myself, will be completely new to this world. Can you give us a basic definition of it?

Alex Mar: This is a funny way of describing it, but in mainstream terms if Paganism is like Christianity, then Wicca are like Catholics, and other traditions like Feri would be Baptists or Methodists. They all share a lot in common, but practitioners take the differences seriously. They have different flavors and liturgies, varying gods and goddesses, but share some theologies like nature is sacred, and male and females are equal in the universe.

BIOG: What was the through line from “American Mysticism” to writing the book?

AM: I made the documentary as a journalist, to explore different belief systems, trying to understand what brings meaning to our lives. We express ourselves in so many different ways, yet some people get so upset about what others subscribe to. I focused on Paganism because it’s growing, it’s a new chapter in the history of religion in this country. Part of the appeal is witchcraft and magic, but I wouldn’t have written Witches of America without looking at how spirituality evolves. I wanted to contribute to an exploration of religion that’s more than the “Christian right” or outrageous stories about the latest cult that pops up. Those two extremes aren’t an accurate depiction of the range of American practices.

I am also interested in people who choose to practice a religion outside the mainstream, because it costs them something. It doesn’t come with the advantages, the social networks and structures of say a popular synagogue or megachurch. If you call yourself a witch or a pagan in many parts of the country, it requires sacrifices. You may not want your neighbors to know. You’ll be identified as an outsider. When I met Morpheus, I realized we have so much in common as people. She’s really sharp, has a great deadpan sense of humor, and has a confidence in her witchcraft practice I was very impressed by. She’s a serious priestess and once the cameras stopped rolling, there was so much more I wanted to know.

BIOG: As someone who was raised in the Catholic church, I found the spiritual-seeking aspect — adults choosing to follow a path outside the mainstream as opposed to what they’re born with — intriguing. Is this the primary reason people become practicing Pagans?

AM: There’s two kinds of human longing that any religious community can satisfy. One is wanting to belong to a social group that you have something special in common with, outside of the practices. It’s human and unavoidable, we want to feel bonded to a group. Like mainstream religions, Pagans or Witches are looking for connection with a particular god or goddess, but it seems alien or exotic because of the baggage we have around the word ‘witch.’ If someone refers to themselves as a witch, the assumption is often that they’re out to do evil. It’s a dramatic word. Most Pagans are polytheists and in this country, we usually only encounter that with Hinduism. Meeting someone who is American-born, who may have been raised in a Christian church, and who believes in many gods and goddesses can be jarring. There also aren’t fancy cathedrals, no fundraisers to construct elaborate architecture. A coven can meet in people’s homes, or in nature, which is one of the wonderful things about it, but for outsiders it can seem like there is no institutional control, that it’s a free-for-all. Who’s in charge? Every individual can have a direct connection with a god or goddess.

BIOG: Is feminism an underlying part of the movement?

AM: In Paganism, there is a belief that of course, women should play important roles in their religious communities. As someone who was raised as a Catholic, a liberal, and a feminist, I’ve always had a major problem with the idea that there would be an end game if I wanted to become a leader. I never considered joining a convent, but it bothers me that there’s a cap to the rites women can perform in the Catholic church. It’s arbitrary, unfair, and ridiculous.

In terms of Wicca specifically, it came over from England in the 1960s, and got going with the counter-culture. In the 1970s, during second-wave feminism, the idea of goddesses was very appealing to women who felt left out. At this point, it’s a bedrock belief that women should have an important role and it’s not even discussed.

BIOG: Some of the rituals you attended seemed right in line with, say, Catholicism, while others had more of a non-religious subculture vibe, more in line with hippie communities, or even a dress-up play-acting group like one might find at a Renaissance Fair. Is that accurate or am I too condescending?

AM: There is theatricality for many practitioners, but events like Ren Fairs don’t have a spiritual element. Every February, witches and pagans take over a hotel for PantheaCon. There are seminars, and rituals in the ballrooms; it’s a great way for people to meet and share practices. There is also the lifestyle element where attendees dress very elaborately and can proudly be an outsider in a renegade way. For young people, it’s part of the appeal, but I don’t think it’s different from kids at a Christian megachurch who go to hang out, play Xbox and eat Krispy Kremes. It’s not a judgment on their devotion, but there are always people who enjoy the social aspect. Costumes are easy to notice, but it doesn’t have a major bearing on the spirituality.

BIOG: There is a section in the book where you describe a number of priestesses, Morpheus included, who had rough lives — abuse, bad relationships, etc. Is finding others who’ve gone through similar circumstances also a draw?

AM: No, not really. The women you mention are in the book because they worship The Morrigan, a Celtic war goddess, and they each told me they were called to her at moments when they were going through trauma, or in a dramatic recovery period. There was a similarity in the way they were called by The Morrigan, in what brought the members together. For me, it’s an interesting look at the idea of a ‘calling,’ which is referenced by all types of religions. Throughout the book, I wonder if I would ever experience a calling to some kind of spiritual practice. I admired the clarity of the women I met.

“The hazy middle ground where you aren’t sure where you stand, maybe throughout your life, is the conversation I want to contribute to.”

BIOG: I was curious about that, as someone who isn’t looking for a spiritual connection and whose Catholicism is long in my past-

AM: But don’t you ever have that need to have clarity in your life or a system that guides your day-to-day? Doesn’t that sound great, even in an abstract way if it wasn’t Catholicism?

BIOG: I found things became much clearer when I dropped the church baggage. Letting it all go did wonders, and it helped in reading the book, because I didn’t have the severe judgments on Pagan practices I would have years ago. To me, pouring pig’s blood on one altar isn’t that far off from turning wine into the blood of Jesus. It’s all ritual, and ridiculous in some ways, to me…

AM: I wrote the book to highlight this growing community that I hadn’t seen before. But I also thought there was something important about exploring my own doubts while showing alternatives rituals and religions. Many of my friends are writers, artists, and intellectuals of one kind or another, and they have an issue with any kind of religious community for whatever reason. I had those people in mind too. I tried to create a grey zone where readers can grapple with these questions, because they’re important. There is a tendency for people to think one day you wake up, have a revelation, and then you have religion. Or conversely, you’re raised in a church, have a revelation, and leave your religion. The hazy middle ground where you aren’t sure where you stand, maybe throughout your life, is the conversation I want to contribute to.

BIOG: At no time though, did your book feel like Eat, Pray, Love, Wicca. Was it hard to keep yourself as a character in the book without overwhelming the anthropological narrative?

AM: Initially, my editor and I thought the book would be straight journalism, using myself as a framing device to place the reader in this world. I quickly realized, it didn’t feel honest. It wasn’t my approach to writing. I wanted the book to be about the bigger issue of faith and meaning, so I had to be upfront about my questioning of myself. It was embarrassing to write about. I was vulnerable, it was hard exposing myself. It was challenge to figure out how to handle those aspects.

But I also knew I was writing for a general audience, not specifically for the Pagan community, and readers need a guide, although not an authoritative one. I didn’t want to be dismissive in any way. I’m on a book tour now and a lot of the questions I get are hilarious. A lot of people want to know what Pagans are up to, and the questions feel like they’re out of the 1950s.

BIOG: Speaking of exposing yourself, there seems to be a lot more sex in Paganism than in your mainstream churches, like the woman who was naked on a throne. Did it take a lot to accept sex as part of a religious practice?

AM: No, not at all. Your talking about the Gnostic Mass, which is a central rite of Thelema, but that’s nudity, not sex. It’s not commonplace, but it was just a naked woman sitting on an altar. We’re prudish about our bodies in this culture, and I’m as conservative as anyone with that stuff, but it’s about showing the naked body is nothing to be ashamed of and can be used in a ritual.

BIOG: Fair enough, bad example. There are other times in the book where it’s a central tenant to the spirituality, like when Morpheus is in the temple practicing “sex magic…”

AM: As a community, Pagans are sex-positive. There isn’t any guilt around it. In fact it’s frowned upon to use sex in a way that hurts someone else. There’s a lot of respect for sex and there isn’t the idea that it’s only for people who are married, or in a committed monogamous relationship. Many Pagans I met are polyamorous. It’s a different set of social values, but it doesn’t mean people are constantly having orgies.

If you think about it, it’s not that strange. Sex is very powerful. Consider the amount of focus we put on sex in this culture and the way it shades everybody’s lives. If you believe magic is real, which Pagans do, it isn’t that big of a leap to see sex as a form of magic. It drives every human being with a pulse to some degree. In my observation though, the practice of “sex magic” is used mainly among partners, it’s not a random bacchanalia.

BIOG: I found the chapter on the Church of Satan illuminating. They seem to be trolls (in the internet sense, not the under-the-bridge kind) as opposed to devotees of the devil…

AM: They’re not even involved in Paganism. I included them because in any conversation about witchcraft, someone mentions Satan. The Church of Satan is basically a bunch of atheists who enjoy invoking that name because it gets a rise out of mainstream America. They’re having fun, but it does get them in trouble because they get linked to people who commit horrible acts and say they were under the spell of the devil. The idea of an organized network of Satanists who want to do horrible things to our kids is totally a myth. In the book, I wrote about the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s-90s, which led to thousands of people being accused of horrific abuse of children. It’s hard to believe it happened, but the idea of a Satanic network still lingers in the background.

BIOG: The chapter where you spend time with Jonathan, a New Orleans necromancer who steals skulls and bones from corpses, is rather disturbing. What do you want readers to understand about him and the practice?

AM: I’m not deluded, I knew that chapter would be controversial, so it took a lot of thought and consideration. I wrote about necromancy in detail because I wanted readers to meet an occult extremist, a label Jonathan would agree with. He is not related in any way to the larger Pagan culture. It’s the radical fringe. He’s bright and well-read and there is a tradition of dealing with the bodies of the dead in this manner that goes back to ancient times, so there’s precedence and a logic to it. It’s shocking in a modern context, but I wanted to give readers a chance to see it from his perspective. He’s not making this up out of thin air, he’s following ancient texts and practices. I also felt it was important to address the question of is there such a thing as “black magic.” Jonathan is a black magician all the way.

BIOG: Now that Witches of America is out, how do you feel about the book?

AM: Big picture, I hope the book helps contribute to a more accurate sense of what it means to call yourself a witch in America. They aren’t horrible insidious hags who want to eat your children. On a more personal level, there is a strong tradition in American publishing of the transformative memoir, someone goes on a spiritual journey and comes out a different person on the other side. It’s a message readers want to hear, but it wasn’t an option for me. It’s often the formula for a bestseller, but life is too complicated. I have too many questions. There is a revelation at the end, but it’s not a clean one. I’m still searching.

BIOG: Lastly: are you still able to enjoy Halloween, horror movies, Stephen King novels, etc. in the same cultural way as the rest of us?

AM: I still find all that stuff incredible fun. I love horror movies and have a real soft spot for 1970s Italian films like the ones made by Dario Argento. Actually, many Pagans have a great sense of humor about Halloween and love all of it too because it is so separate from their religion.

The one difference is that this time of year has a deeper meaning for me. I see the spooky macabre fun a little differently now. While we’re out doing Halloween up with pumpkins, candy, costumes, and decadent parties, nearly a million Americans will be celebrating Samhain. People connect with loved ones they’ve lost, or ancestors, and honor them with offerings. It’s when the veil is lifted between this world and the next.