Memoir in a Melody: The Outrage in Nina Simone’s ‘Mississippi Goddam’

By Matt Staggs

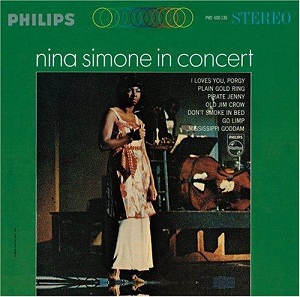

Simone at a concert in Morlaix, France, May 1982

In our Memoir in a Melody series, Biographile writers examine the storytelling of well-known musicians, exploring the autobiographical elements of their famous songs.

On a cool March night in 1964, musician Nina Simone debuted a song that would change her career, complicating her relationship with the white establishment while cementing her allegiance with the civil rights movement. The song was "Mississippi Goddam," and Simone performed it live at New York City’s Carnegie Hall. It would become a civil rights anthem.

Carnegie Hall was thousands of miles from the racial turmoil of the Deep South, but Simone was determined to bring a taste of the era’s injustice to her mostly white audience, at least some part of which had probably come to hear lighter fare like "My Baby Just Cares for Me" and "I Loves You Porgy."

Simone introduced "Mississippi Goddam" by describing it as "a show tune, but the show hasn't been written for it, yet." The song does indeed sound like a show tune, at least for a few moments, and during that time one can easily imagine Simone’s audience letting their collective guard down just long enough for the anger of its message to take root.

Simone opens the song with the couplet "Alabama’s gotten me so upset, Tennessee’s made me lose my rest." Both states had been, and would be, major battlegrounds in the war for civil rights.

Less than a year earlier, members of the Ku Klux Klan had bombed Birmingham, Alabama’s 16th Street Baptist Church: an African-American church that had been an informal center for the Civil Rights movement in the city. Twenty-six children were caught in the blast. Four girls, none of them older than fourteen, were killed.

In 1960, Nashville, Tennessee's activists had staged city-wide "sit-ins" to protest segregation at area diners and boycotted local businesses that engaged in racially unjust practices. Protesters faced retaliatory violence and mass arrests, including the bombing of the home of civil rights lawyer Z. Alexander Looby.

After name-checking Alabama and Tennessee, Simone turns her attention to Mississippi: "And everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam." Whether she means "Goddam" as a rebuke or an expression of her exasperation doesn't really matter: The state had easily earned both through decades of cruelty and violence waged against its African-American citizens. Many activists were abused, tortured and even killed with the approval, implicit if not overt, of the state's lawmakers and civil authorities. Among the victims was Medgar Evers.

Evers was a World War II veteran turned high profile civil rights activist; a man unafraid of confronting the injustice around him, no matter the cost. As a president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership and organizer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Evers was instrumental in the state's civil rights movement. As a result, he became a target for white supremacists to silence. Refusing to bow to intimidation and threats, he paid for his bravery with his life. He was assassinated in the driveway of his Jackson, Mississippi home on the morning of June 12, 1963. Evers’s assassination horrified many, among them Simone, who composed "Mississippi Goddam" largely in response to the event.

Listening to the song, it seems like Evers’s murder could have been a breaking point for Simone; an acknowledgment that things have gone past a point of no return, Simone having lost her ability to deal with the horrors around her:

Can't you see it

Can't you feel it

It's all in the air

I can't stand the pressure much longer

Somebody say a prayer.

For Simone, the "show" that "Mississippi Goddam" was written for might just be the collapse of a society built upon injustice:

This is a show tune

But the show hasn't been written for it, yet

From there, the song’s lyrics begin to take an almost apocalyptic tone. The fear and anger has become palpable, and bad omens abound. Simone makes a little call-back here to the Delta blues: the line "Hound dogs on my trail" is very similar to the title of bluesman Robert Johnson’s song "Hellhound on my Trail." Another bluesman, Howlin’ Wolf, sang about black cats crossing his path in "I Ain’t Superstitious." Both Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf were Mississippi natives, and she intersperses their narratives with her own politically-toned brand of blues.

Hound dogs on my trail

School children sitting in jail

Black cat cross my path

I think every day's gonna be my last.

She’s a woman without a country, and she has lost her roots.

Lord have mercy on this land of mine

We all gonna get it in due time

I don't belong here

I don't belong there

I've even stopped believing in prayer.

After venting her personal frustration, Simone turns a scornful eye upon a society that is reaping benefits from allowing injustices to continue. "Do it slow," she sings, mocking the South’s reticence to move on federal civil rights legislature while at the same time providing a litany of demands and insults foisted upon African-Americans by those who oppress them.

At this point, one can presume that Simone knew that her white audience must be squirming, as she acknowledges it with this line:

I made you thought I was kiddin' didn't we.

Simone still has plenty left to address, though, including the FBI’s anti-civil rights Counter Intelligence Program, also known as "COINTELPRO." The bureau’s COINETELPRO efforts were aimed at discrediting civil rights leaders and the movement as a whole, and one of its strategies was to depict their activities as part of a communist plot. Simone references it here:

Picket lines

School boycotts

They try to say it's a communist plot

All I want is equality

for my sister my brother my people and me.

With this final bitter accusation still wafting in the air, the song offers an foreboding warning before returning to the chorus.

Oh but this whole country is full of lies

You're all gonna die and die like flies

I don't trust you any more

You keep on saying "Go slow!"

The final verse of the song is desperate; a plea for a minimum of parity in a white-dominated society.

You don't have to live next to me

Just give me my equality

Everybody knows about Mississippi

Everybody knows about Alabama

Everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam.

Simone closes with one line:

That's it for now! See ya' later

That line would prove prophetic in many ways, because “Mississippi Goddam” didn’t only mark a turning point in her relationship with her white fans, it also signified a growing frustration with America in general. Simone left the country for good in 1970, eventually settling in France where she died in 2003.