Muffled Voices: 5 Famous Authors of Banned Books

By Jennie Yabroff

In 2008, when Phillip Pullman learned his novel, The Golden Compass, was one of the most banned public library books in the country, his reaction, he said, was "glee." Not only did the ban mean free publicity, but guaranteed an increase in sales, as readers who might otherwise check his book out of libraries would now be forced to buy it from bookstores. Today, when most writers are grateful to get attention -- any attention -- for their books, and Fifty Shades of Gray has grandmothers reading about S&M, libraries and school boards across the country still challenge the inclusion of books they consider dangerous or subversive.

Paradoxically, many of the most celebrated writers of the 20th century have had their books banned at one point or another, usually because the language or ideas were deemed unsuitable for impressionable minds. Of course, these same books have gone on to become staples of high school reading lists, proving that, perhaps, with time, writers like Pullman (and Suzanne Collins, and Stephen King, and John Irving, all of whom have seen attempts by school libraries to ban their books) will become part of the high school canon as well. To check out some noteworthy banned authors in honor of banned books week, read on.

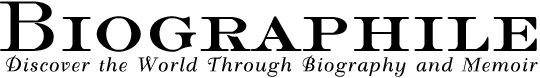

Mark Twain by Geoffrey C. Ward, Ken Burns, and Dayton Duncan

In 1885, the public library of Concord, Massachusetts decided to ban a new novel by Mark Twain: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which the committee objected to on the grounds of improper grammar and salty language. Twain, in usual fashion, had a sardonic reply, archly agreeing that his novel was unfit for children, since he had been irreparably harmed himself by reading inappropriate material as a child: the Bible. In this biography, the writers describe Twain’s life and unlikely role as the poster boy for banned literature.

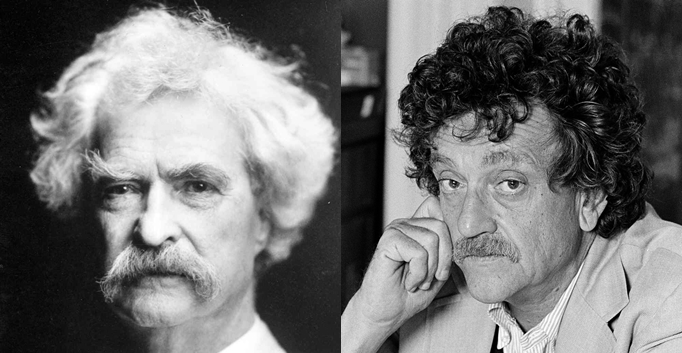

Kurt Vonnegut: Letters by Kurt Vonnegut

In his fiction, Vonnegut could be sardonic, sarcastic, and outright hilarious, but he took it seriously when school boards tried to ban his work. In this collection of his letters, he writes impassioned letters in defense of his novel Slaughterhouse Five, which censors have deemed immoral because of profanity and sexuality. In 1973, after a North Dakota high school burned copies of the book, Vonnegut wrote the principal: "Certain members of your community have suggested that my work is evil. This is extraordinarily insulting to me. The news from Drake indicates to me that books and writers are very unreal to you people. I am writing this letter to let you know how real I am."

Salinger by Shane Salerno and David Shields

Thirty years after its publication, JD Salinger’s famous novel, The Catcher in the Rye, was the most censored book in public high schools in America. It was also the second most taught book in high schools. Objections to the tale of Holden Caulfield’s sojourn in New York City range from the amount of smoking in the book to the antisocial nature of its main character, and its continued status as a controversial novel should ensure its popularity for years to come. In this new biography, Shields and Salerno describe Salinger’s life pre and post Catcher.

Steinbeck: A Life in Letters by John Steinbeck

Usually, censors seeking to ban books object on moral grounds, but in the case of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, the decision was purely political. When the novel, which depicts the poor migrant worker Joad family facing hunger and hardship in Kern County, California, was published, the Associated Farmers took offense and held a public book burning. Steinbeck, they claimed, was a socialist who exaggerated the conditions the Joads faced, and his book was a work of left-wing propaganda. In this collection of letters, we see Steinbeck’s true goals for his works, including the also-banned Of Mice and Men.

Mockingbird by Charles Shields

Harper Lee, the author of To Kill a Mockingbird, may be notoriously close-mouthed on the subject of her deeply beloved novel, but she had plenty to say (or, rather, write) when the school board in Hanover, Virginia, decided to ban her book in 1966. In a letter to the editor of the local paper, Lee wrote, "To hear that the novel is 'immoral' has made me count the years between now and 1984, for I have yet to come across a better example of doublethink…I feel, however, that the problem is one of illiteracy, not Marxism. Therefore I enclose a small contribution to the Beadle Bumble Fund that I hope will be used to enroll the Hanover County School Board in any first grade of its choice."