Revealing the Rebellious Rothschild: A Q&A With Hannah Rothschild

By Joanna Scutts

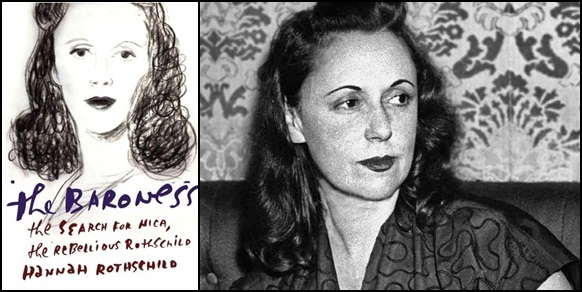

Nica in London's Stork Club in 1954/Photo © Marcus Harrison

In her biography, The Baroness, Hannah Rothschild sets out to discover the truth about her great-aunt Pannonica, "the rebellious Rothschild," nicknamed Nica -- a child of stifling wealth and luxury who abandoned her former life and family when she became captivated by the music of Thelonious Monk. In her later years, Nica lived in New York as a patron, muse, and guardian of Monk and his circle, a white, Jewish, middle-aged baroness who had given up her children for the love of jazz. She was a riddle whose solution lay deep in the buried history of the Rothschild family.

Biographile: You've previously made a radio program and a documentary about Nica's life. How was writing the biography different from those projects -- and why did you choose to extend the story in this way?

Hannah Rothschild: It was partly that I couldn’t bear to let her go; partly because I had unearthed so much more extraordinary, revelatory information that never made it into the radio program or documentary. In a book there is more time and scope to explore the undercurrents and byways. As I wrote, though, I realized that in many respects it was like starting all over again -- radio programs and documentaries require a totally different type of storytelling. A good thing perhaps, as I never got bored!

BIOG: I was struck by the contrast between Nica's wealth and the rigid constraints imposed on her as a female Rothschild: Although she was surrounded by money, she had control over very little of it. How do you think that tension between wealth and gender shaped her life?

HR: Nica described her cosseted, privileged childhood as like being stuck in a jewel-encrusted cage. She had little freedom and few choices: Her childhood was simply a training ground and holding pattern for motherhood and marriage. When she met her husband she was only twenty-one, and she was expected to replicate her earlier life. I'm not sure if the tension was between wealth and gender -- I think it had more to do with expectation and emancipation. She simply couldn’t stand to live in a world of rules and regulations, shoulds and should-nots. She wanted more freedom -- and she got it.

BIOG: At one point (in a wonderful phrase) you describe Nica as the "Miss Havisham of bebop." She often comes across as a fundamentally lonely person, who gave more to her friends than they gave her in return. Do you think that's a fair assessment?

HR: I agree that Nica was a rather lonely figure who gave more than she got. She ran around after Monk and other musicians and asked for little in return. However, they gave her the one thing she had always craved -- friendship -- as well as a front-row seat to the one thing she loved above all else, jazz music.

BIOG: You often allude to the difficulties of researching your family, given their routine destruction of personal papers and overriding desire for privacy. How did you work around those gaps in the archive, and how did they affect your writing of Nica's life?

HR: I think that a biographer has to be a detective, a historian, and when the facts fail, [a biographer] has to enlist the powers of a novelist, asking a novelist's questions: Who is this person, what did they do, and why? How much are they shaped by society and circumstance or by fate? Of course, we can never know a person a hundred percent even if they are sitting next to us, but we can make informed guesses. I used these methods on the gaps.

BIOG: You write at one point that you were initially hoping Nica -- "the rebellious Rothschild" -- might be a role model for you. Is that still the case? How do you feel about her now?

HR: I think rebelliousness is a trait that belongs to the young -- I am much too old for all that now! Now that I've had children of my own, Nica is no longer a role model. But I often think of her maxims: "Throw your heart over the fence and the horse will follow" and "Remember there is only one life."

BIOG: How is Nica perceived today in the jazz world? Is she considered an important part of its history, or still dismissed as a groupie?

HR: I hope and believe that Nica is remembered as someone who dared to make a difference.

BIOG: You write movingly at the end of the book about your feelings of regret and wistfulness at finally letting go of Nica. Do you have a new project in view?

HR: I am writing a fictional novel set in the art world -- no more facts, no more family!

BIOG: How was the book ultimately received in your family?

HR: Funnily enough, the only two complaints I had from family members after the book came out is that they thought they were the rebellious Rothschilds!