Tales of Atrocity: From the ‘SS’ to ‘ISIS’

By Timothy Ryback

Editor's Note: Timothy W. Ryback has written for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times. He is the author of Hitler’s Private Library, which was named to the Washington Post Book World Best Nonfiction list in 2008, The Last Survivor: Legacies of Dachau, a New York Times Notable Book, and most recently Hitler's First Victims. He joins Biographile to tell the story of Hartinger, one of the earliest opponents to Nazi Germany, whose actions demonstrate the transcendent power of the law, as worth remembering today as it was some seventy years ago.

Last August, the US Justice Department vowed to bring to justice an unnamed suspect in the beheading of the American journalist, James Foley, in Syria. “We have an open criminal investigation,” Attorney General Eric Holder Jr. said. “And those who would perpetrate such acts need to understand something. This Justice Department, this Department of Defense, this nation … we have long memories and our reach is very wide."

Quixotic as this legal gesture may seem given the state of chaos in the region, and the subsequent atrocities that have followed, history offers comforting evidence for Eric Holder’s assertion about the transcendent power of justice.

In June 1933, a local Munich prosecutor issued a murder indictment and arrest warrant against the SS commandant and "unnamed" perpetrators for the killing of detainees in the Dachau Concentration Camp. The thirty-nine year old prosecutor, Josef Hartinger, knew it was a perilous legal act. Adolf Hitler was chancellor and Germany was under Nazi control. But like US Attorney General Holder, Hartinger trusted in the transcendent power of the law.

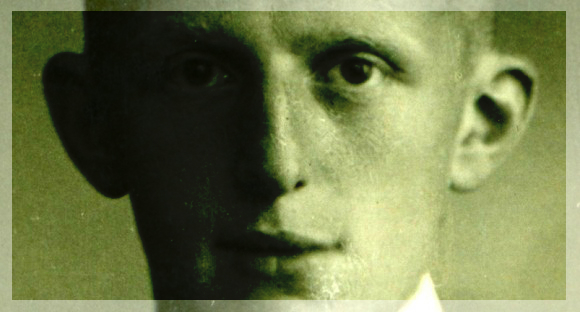

Twelve years later, after the defeat of Nazi Germany, the Hartinger indictments served as key evidence at the Nuremberg Trials in declaring the SS a criminal organization, and in ultimately identifying and bringing to justice Hans Steinbrenner, one of the unnamed perpetrators. In spring 1933, Steinbrenner was a twenty-six year old, unemployed high-school drop-out with blond hair, striking blue eyes, and a seemingly limitless capacity for savagery. As a freshly recruited SS guard, he flogged one Jewish detainee until his bones were visible, then casually watched him die. Steinbrenner executed another Jewish detainee with a single bullet to the head. Dachau inmates nicknamed him "Mordbrenner," the murder man.

When Hartinger learned of the first killings in the Dachau Concentration Camp in April 1933, he used his legal authority to enter the camp and collect evidence. He suspected something sinister from the outset. “My reasons were based not only on the physical circumstances but in particular on my evaluation of the camp commandant Wäckerle who made a devastating impression on me,” Hartinger later wrote. “I also had to include in my deliberations the fact that all those who had been shot were Jews.”

As the killing escalated, Hartinger pressed his investigations. He collected evidence, working with a forensic medical expert, Dr. Moritz Flamm, who conducted detailed autopsies of the victims and provided incontrovertible evidence of homicide. Hartinger was relentless despite obstruction by the camp commandant, threats from the guards, and warnings from his own colleagues in the prosecutor’s office. When one guard stopped him at the camp entrance and threatened to shoot if he entered, Hartinger replied, “Then you will have to shoot me. I am coming in.”

Hartinger assembled his cases meticulously, systematically, resolutely. He was able to implicate the camp commandant, the camp administrator, and the camp doctor for complicity in four murders, and to identify several perpetrators by name. Where he lacked evidence, he simply listed “unnamed” suspects. Hartinger was well aware of the risks he was taking. The night he signed the murder indictments and arrest warrants, Hartinger told his wife, “I just signed my own death sentence.”

Astonishingly, the killings in Dachau stopped. Hartinger had hurled a legal wrench into the Nazi bureaucracy. Indeed, the murder indictments and arrest warrants were so complicating that they eventually found their way to the desk of Adolf Hitler who ordered the proceedings quashed. In December 1945, twelve years and tens of millions of deaths later, the Hartinger investigation files were presented to the judges at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. They also helped identify Hans Steinbrenner as one of the “unnamed” perpetrators in the first killing of Jews in Dachau, the beginning of a homicidal, chain-of-command process we have come to know as the Holocaust.

During one of his pretrial interrogations, Steinbrenner spoke of the concern that he and his fellow SS guards had initially felt following the execution of the first Jewish detainees in Dachau. The SS guards had worried that they could be held accountable for the killings when Hartinger first arrived, but were relieved when the prosecutor’s superior prematurely closed this first case of killing. It was only then, believing themselves beyond the reach of the law, that the SS guards felt empowered to unbridle their full capacity for atrocity.

“I need to note that back then if the police commission from Munich, which on such occasions conducted inspections of the crime scene and other investigation, had been more thorough and decisive, ” Steinbrenner confessed, “they would have determined that these Jews had been murdered, not shot trying to escape. This would have had the consequence of preventing further and similar transgressions.”

The Steinbrenner confession is a chilling indictment of the human potential for violence. Steinbrenner felt empowered by a fanaticized government and protected from accountability by a political system that claimed that it would last a millennium. In the end, the Third Reich collapsed after twelve brief and bloody years, leaving its surviving perpetrators to account for their actions before a court of law. Like Prosecutor Hartinger, Attorney General Holder trusts that a system based on rampant fanaticism and violence cannot last or long endure, and that when it does collapse the perpetrators, both named and unnamed, will be held accountable for their transgressions.