The Invisible Front: What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About War

By Jennie Yabroff

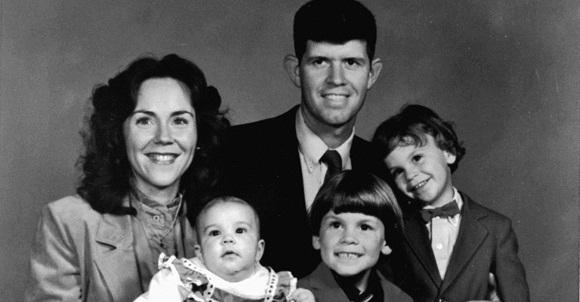

The Graham Family

In his new book The Invisible Front, Yochi Dreazen writes that "soldiers have buckled under the strain of witnessing and committing horrific acts of violence for as long as humans have taken up weapons against one another." From the time of Achilles' suicidal despair in The Illiad, through the shell-shocked troops of World War I, followed by the traumatized vets of Vietnam, and continuing with the soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with their psyches in tatters, post-traumatic stress has gone hand-in-hand with war, though it has only recently gotten the official title of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

In his book, Dreazen, a deputy editor of Foreign Policy who has reported extensively on Iraq and Afghanistan, tells the story of the Grahams, a military family who lost one son, Kevin, to suicide while he was still in ROTC, then lost their second son, Jeff, less than a year later when he was killed by an IED in Iraq. In telling their story, Dreazen examines the continuing stigma against mental illness in the military, the enormous toll PTSD is taking on our troops, and the epidemic of suicide that, in some cases, may end up costing more lives than war itself. He spoke to Biographile about his book.

Biographile: How did you first learn about Carol and Mark Graham and their sons?

Yochi Dreazen: I profiled Carol and Mark for the Wall Street Journal a few years back and stayed in close touch with them. I had a couple of close friends who were suffering from PTSD and, in a few cases, committed suicide. The Grahams and I talked about doing something bigger than the article as the suicide rates continued to rise. Because I had spent so much time with them and had gotten to know them as friends, they trusted me to write about this horrific part of their life carefully and compassionately.

BIOG: And for that original article, were you interested in suicide in the military and used the Grahams as a way to explore that issue, or did you hear about the Grahams and then discover the epidemic of suicide as your told their story?

YD: I had heard about the suicide epidemic because it was hitting people I knew. I mentioned to an officer my concern, and he said he himself had suffered with PTSD and depression. He paused, you could tell it was difficult for him to even talk about it, and then he said, there’s this general in Colorado who lost his two boys. I got on a plane to Colorado, spent hours talking to them in their living room. I thought of myself as a tough guy, I’d been to war, but as I was talking to them, I kept saying I had to go use the bathroom so they couldn't see I was crying myself.

BIOG: Was it difficult for you to get military personnel to go on the record?

YD: I've spent time with a lot of generals, and some of them would say they knew they had some issue but wouldn't use the phrase PTSD, even though they had all the symptoms of PTSD. When I would say, can I use your story in the book, none of them would do it except one. On the flip side, former Defense Secretary Bob Gates, who is kind of this stone-faced guy from Kansas, when I interviewed him for the book he told me that by the end of his time as Defense Secretary he himself had some form of PTSD after going to so many funerals and seeing so much human carnage so close. I found that extraordinary.

BIOG: Was reporting the book traumatic for you as well?

YD: When I came back from a long bloody stretch in Afghanistan, I had flashes of temper and I couldn't sleep and I had horrible dreams. It took me a while to accept I had PTSD. I wasn't suicidal, but it was terrifying to me. Friends would say, Yochi, you sound scary. Finally a friend made me see a psychiatrist. Now I’m on medication that changed my life. Therapy can help, too, but it’s not perfect. Even if you have the most compassionate civilian therapist and a soldier willing to talk, they can’t fully understand each other. It’s really easy for a soldier to think, you can’t understand this, you’re a civilian, you’re weak. And even in places where they have resources, a lot of people still are afraid to use them.

BIOG: A lot of the statistics in this book may surprise civilian readers. What was the most surprising new piece of information you learned in your reporting?

YD: The fact that well over over 2,000 lives have been lost to suicide in these wars, which is more than the people who have died in Afghanistan. We think, America goes to war equals Afghanistan and Iraq. We forget there’s this third war that has caused more deaths than Afghanistan did. I was also surprised to learn about the proportion of soldiers who, all these years later, still feel they can’t see a psychologist because it will harm their careers. Everyone from the president on down has tried to eliminate the stigma but it’s still there.

BIOG: You imply that Kevin Graham’s decision to stop taking Prozac because he feared he would be kicked out of ROTC contributed to his suicide. But you also say the military should limit troops’ access to prescription drugs.

YD: Prescription drug access raises the risk of suicide on two ends. All medication, when you read the fine print, when you first start taking it you need to be under close supervision because it causes a spike in suicidal thought. And these guys are not being supervised. And there’s very little oversight of how much they’re taking. I was on a base where a military doctor did a survey of how many soldiers were on medication and what they were taking. Everyone was on medication. They’d say, I’m on Xanax and I take 9 a day. Or, I’m on Ambien and I take 6 a day. Which are incredibly high dosages. Then they come to the US and have to go off the drug entirely or greatly reduce their doses and they’re at great danger. But the bigger issue, frankly, is alcohol abuse. Getting alcohol in Afghanistan was hard, then they’d come back and spend weeks drinking themselves out of their minds, and that’s what pushes them over the edge.

BIOG: You write that PTSD has existed by one name or another as long as war has existed. Is it realistic to think we can send people into battle and not expect them to be psychically damaged by the experience?

YD: No. I don’t think it is. One of the quotes I found very powerful is that if you go to war and you see combat and you see your friends die and you come back and you’re not changed, that’s where there’s something very wrong with you. When we talk about the way war is fought now, you have armed drones piloted by people in an air-conditioned trailer in Nevada. But they suffer PTSD too. Even the people who are not in physical danger, they are suffering invisible wounds too. It’s been this way in the past, and it will be that way well into the future.

BIOG: Do you think leaders need to take the psychological cost into account when deciding whether to enter conflicts in other parts of the world?

YD: To put it coldly, people in the Pentagon have to look at the financial cost. Treating soldiers who have PTSD for the rest of their lives is enormously expensive. If you came back and you’re wounded, even if that wound isn't being in a wheelchair, people need to have that in mind as the cost of war. The number that come back and can’t sleep or punch their wife or drive their car off a bridge twenty years later, that’s part of the full cost of war.