Things I Don’t Want to Know: Deborah Levy on the Political Purpose of Female Writers

By David Burr Gerrard

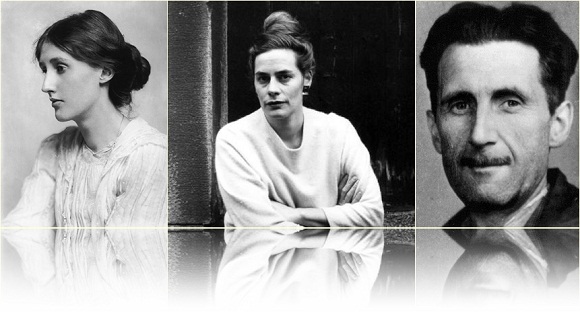

The subtitle of Deborah Levy’s new memoir Things I Don’t Want to Know is On Writing, and the cover depicts a notebook, but readers looking for practical or inspirational writing advice suitable for quotation on Tumblr will come away disappointed. So too will anyone looking for direct engagement with George Orwell, though this book was written as a response to George Orwell’s classic essay "Why I Write." Levy takes the reasons that Orwell gives for why he writes -- "sheer egoism," "aesthetic enthusiasm," "political purpose," "historical impulse" -- and seems to use each as an occasion to write about whatever moment from her life is on her mind (though a pattern slowly reveals itself). Sometimes this means writing about crying on escalators; sometimes this means writing about her strange, past-haunted flirtation with a man she identifies only as "a Chinese shopkeeper"; sometimes this means writing about the nanny, a moonlighting graduate student, who offered this justification for hitting her brother: "He was banging the drum while I was translating Marx’s essay on wage labour written for the German Working-Man’s Club in Brussels." Rather than, say, telling the reader to show rather than tell, she declines to tell us anything and then shows us a great deal.

What results is much more valuable than any literal writing guide or any literal response to Orwell would have been. It certainly has greater political import. One of the few times she mentions Orwell directly, she questions exactly what he means by "sheer egoism," which Orwell acknowledges is unavoidably present in all writers, and most of all in serious writers, but which he implies good writers must struggle against. Levy retorts: "Perhaps when Orwell described sheer egoism as a necessary quality for a writer, he was not thinking of the sheer egoism of the female writer." Everything in our society tells women to subjugate themselves to the demands of men and children. It is difficult, Levy suggests, for a woman to acquire and develop an ego at all. When a woman talks about her own experience, then, she necessarily has a political purpose. Political purpose and sheer egoism are simply impossible to separate.

Levy’s life is hardly lacking in what would universally be considered high-stakes political drama -- in the early 1960s, her father was arrested and tortured for dissenting from the South African apartheid regime, and she was sent for a time to live with another family. This family’s father is a vile racist, and the daughter is shallow and condescending. The chapter Levy writes on this time is terrifying and unforgettable; another writer with Levy’s background who had been given the assignment to write an essay in response to Orwell’s might have focused entirely on apartheid South Africa. But Levy’s instincts are deeper, and she knows that her political purpose lies in telling the truth about her life in a way that risks being dismissed as sheer egoism by those who aren't paying attention. When Levy’s writing wanders -- from a play she saw in Poland to a playground where she sat with other mothers to some thoughts on George Sand in Majorca -- that is because seizing the prerogative to wander is precisely the point.

Another great work hangs over Things I Don’t Want to Know: Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Levy shares with Woolf a conviction that for a woman to speak is an act of political defiance. But if she takes a stirring stand in favor of the political nature of the interior life, she also wants to emphasize the female writer’s right to take on as vast a portion of the world as she wishes, which is why she ends this brief, bracing, pointedly idiosyncratic book with this sentence: "Even more important for a writer than a room of one’s own is an extension lead and a variety of adapters for Europe, Asia, and Africa."