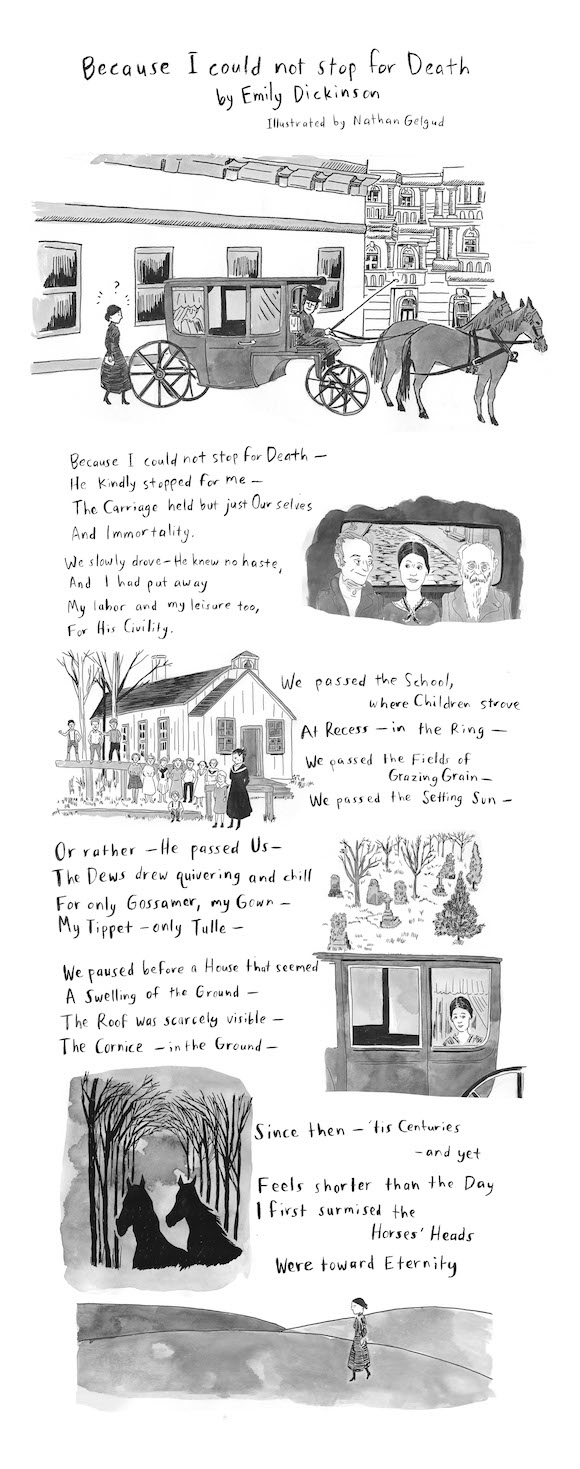

Wish Come True: An Illustrated Emily Dickinson Poem For Her Birthday

By Nathan Gelgud

Emily Dickinson by Nathan Gelgud, 2014.

It's Emily Dickinson's birthday, so I'm thinking of a scene from Woody Allen's 1989 movie Crimes and Misdemeanors. Competing for the affections of Mia Farrow's character, Allen quotes the opening of Dickinson's poem "Because I could not stop for Death":

Because I could not stop for Death—

He kindly stopped for me—

Allen's character starts to point out the effectiveness of that adverb "kindly" when he's interrupted by his rival, played by Alan Alda, who can quote the poem at length to a fawning Farrow.

Allen doesn't get the girl, but he wins a little victory with this viewer. While Alda has the thing memorized (big deal), Allen is interested in Dickinson's word choice. Below, I've illustrated the poem, and got similarly interested in Dickinson's diction as I tried to figure how to create a loose visual interpretation of it. A little tip: If you're ever stumped by a poem, try to draw it.

That word "kindly" is a fitting key for what makes this poem work so well, the way it walks the line between fear of the great void and acceptance of its inevitability. The narrator observes the simple pleasures of the passing landscape, like children playing in the school (I've repositioned them to watch her pass), while the night grows colder and she moves toward her final resting place. Death's pleasant manner with her makes the poem both comforting and chilling.

It makes sense that Allen would name-check Dickinson: as I was digging into the poem, I began imagining it as a scene in his Love and Death or Deconstructing Harry. Despite the frequent characterization of Dickinson as a depressed shut-in, there's a sense of humor in this poem that I might have missed if I hadn't had to read it carefully.

As for that take on Dickinson as a morbid downer, she may have just been someone who wasn't keen on enacting what was expected of a nineteenth-century Amherst woman. It was common at the time to elevate one's community status by going on visits and receiving callers. Dickinson wasn't into this kind of thing, nor was she much interested in marriage or the household duties expected of a woman. So she mostly stayed home, baked bread, and wrote lots of poetry, which she collected into what were essentially nineteenth-century versions of zines, sewing together little booklets and copying her oddly formatted, cryptic verse into them.

Her hang-up with death could be expected – she lived at a time when people would succumb to things like "brain congestion" – but what she did with it is almost incomparable. Unpublished in her lifetime, Dickinson's playfulness with form, her innovative use of first-person, and her way of making the metaphysical feel both quotidian and vast makes her work some of the best and most important American poetry ever written. Happy birthday, Emily Dickinson, from all of us to whom Death has been kind enough not to stop for just yet.