Wonderful Quips and Quotes from H.L. Mencken, the Sage of Baltimore

By Joanna Scutts

One of the most quotable writers of the 20th century, there are plenty of Mencken-isms we may know without knowing they started with the Sage of Baltimore. We quote him when we want to sound worldly-wise -- "For every problem, there is a solution that is simple, neat, and wrong" -- or cynically superior: "No one in this world ever lost money underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of the plain people." There’s no doubt that Mencken’s denunciations -- of politicians, religion, and populist democracy -- can be refreshingly blunt. But as if proving the cliché that inside every cynic is a trapped idealist, Mencken could be passionate in his own way. "You can’t do anything about the length of your life," he said, "but you can do something about its width and depth."

The Library of America has just released an expanded edition of The Days, the autobiographical trilogy that Mencken first published between 1940 and 1943. The trilogy, which Mencken continued to expand and revise throughout the rest of his life, has its roots in an essay he wrote about his Baltimore childhood for the New Yorker in 1936. The piece was a hit with readers, revealing a softer, more nostalgic side to the acerbic critic who was famous for his outspoken coverage of, among other landmark events, the Scopes "monkey trial" (as Mencken dubbed it) in 1925. The three parts of the autobiography, Happy Days (1940), Newspaper Days (1941) and Heathen Days (1943) chart the progress of this unique literary talent from his cocooning, wealthy childhood, through his early years as a journalist and his role, from the mid-twenties on, as one of the country’s best known and most controversial columnists. We rounded up a few more of our favorite Mencken quotes, along with suggestions for further reading on his favorite topics.

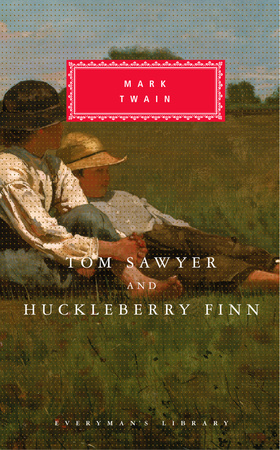

Mencken was a great believer in individualism, in politics and life. He understood the power of the dissenting voice, and prided himself on his own: "The most dangerous man to any government is the man who is able to think things out for himself, without regard to the prevailing superstitions and taboos." While Mencken admired Nietzsche, he was appalled by the rise of fascism in Europe between the wars -- and for him, the quintessential rebellious freethinker was not a politician but a fictional American boy. Mencken recalled reading Huckleberry Finn at the age of nine, and judged it "the most stupendous event in my life." We’re sure Mencken would have loved to delve into the two-part (so far) Autobiography of Twain, a wide-ranging collection of writing and speeches that exhibit the writer’s boundless curiosity and deep skepticism of politicians that he shared with his twentieth-century disciple.

Plenty of modern journalists who are keen on irreverence and whiskey owe a debt to Mencken -- perhaps none more so than the late Christopher Hitchens, who shared Mencken’s admiration for science and disdain for religious faith (the latter famously defined Puritanism as "The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.") Hitchens was no more conciliatory in the title of his 2007 book God is Not Great which attacks the personal and political damage wrought by organized religion, and in its place, celebrates the ascendance of atheism.

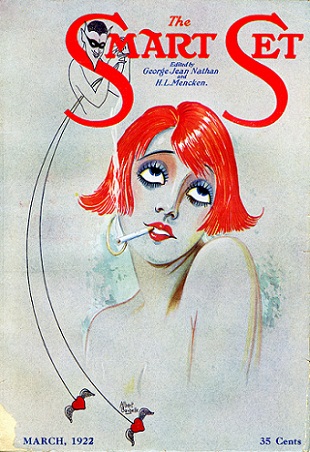

George Jean Nathan, Mencken’s collaborator on the quintessential Jazz Age intellectual magazine The Smart Set, was himself a quotable cynic, known for lines like, "Patriotism is an arbitrary veneration of real estate above principles" and "I drink to make other people interesting." He and Mencken gave a start to many writers in their magazine, from Edna St. Vincent Millay to F. Scott Fitzgerald, but their satirical outlook eventually capsized the publication. When President Warren G. Harding died suddenly in 1923, the editors planned a bitingly irreverent story, fueled by their disgust at the way other newspaper editors were waxing sentimental over a politician they had lambasted in life. The paper’s owner refused to print the piece, and Mencken and Nathan went on to found the literary magazine The American Mercury together, but their partnership was short lived. Thomas Quinn Curtis’s book The Smart Set recreates the world the two editors built, exploring their booze-fueled friendship with the many writers whose careers they launched.

Throughout his years as a literary tastemaker, Mencken continued to work as a reporter and columnist for the Baltimore Sun -- whose limping downfall is charted by another of its former journalists, David Simon, in Season Five of The Wire. Perhaps it’s best he didn't live to see that.

Mencken was well known as a cynic about women and romantic relationships (or as he once put it, "Happiness is the china shop; love is the bull.") So his friends and readers were astonished when he began to woo Sara Haardt, a professor at Goucher College in Baltimore who was almost twenty years younger than he was. Haardt was a talented and prolific writer of fiction, poetry and essays, and her husband -- she and Mencken married in 1930 -- was a champion of her work. But Sara suffered from tuberculosis, and died tragically young in 1935, leaving Mencken bereft. He worked to publish a collection of her writing after her death, and although most of her work is now out of print, the collection Southern Souvenirs (Haardt was originally from Alabama) showcases her literary talents.